#226

Introduction: Understanding the Landscape of Risk and Chance

The recent cancellation of an open-field event due to a lightning threat (Todd Conklin mentioned today in his podcast) highlights an essential concept in Environmental Health and Safety (EHS): the distinction between risk and chance. Although the actual risk of lightning might have been low, the event organisers chose not to take any chances, prioritising safety over probability.

This distinction is often overlooked but is essential for EHS leaders, especially in high-stakes environments. My aim in this post is to demystify the concepts of risk and chance, examine how they impact safety decisions, and offer practical strategies for organisations to create safer, more resilient systems.

Defining Risk and Chance: A Fine Distinction

What is Risk?

Risk in EHS is the probability of an undesirable outcome, typically based on past data, incident reports, and statistical analysis. It is something we can measure, assess, and manage. Risk allows us to use data-driven insights to determine the likelihood of an event, enabling informed, proactive decisions.

What is Chance?

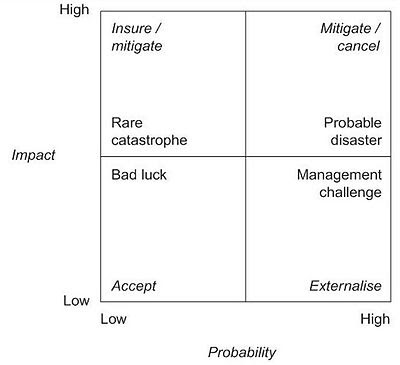

Chance, on the other hand, is more unpredictable and often lacks the structure of past data or consistent outcomes. It’s the wild card in safety management, the unexpected variable that may arise without warning. When we address chance, we acknowledge that even a remote possibility should sometimes be taken seriously, especially when consequences could be severe.

Why the Distinction Matters

This difference may appear subtle, but it is crucial in EHS decision-making. Risk allows us to work with probabilities, but chance highlights the rare and sometimes random. As Tod Conklin’s example shows, understanding both concepts equips organisations with the knowledge to take a “better safe than sorry” approach when needed, balancing caution and pragmatism.

Example: Consider a chemical plant facing a forecast of minor storms. The risk of a major incident may be low, but the chance of a lightning strike, though small, might lead management to temporarily halt outdoor activities. This decision is based on minimising “chance,” despite low risk, prioritising safety over statistical odds.

Risk Identification and Evaluation: Core Tools and Strategies

Structured Risk Assessments

Identifying and evaluating risk is central to proactive EHS management. Techniques like Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (FMEA), Hazard and Operability Study (HAZOP), and Job Hazard Analysis (JHA) offer structured approaches to identifying potential hazards.

These assessments help dissect complex systems, enabling organisations to understand where risks may arise and assess their likelihood and severity.

Using Historical Data and Environmental Conditions

Collecting historical data on incidents, near-misses, and environmental conditions informs risk assessments and gives context to our understanding of potential hazards. This data-driven approach allows for detailed risk profiles and helps identify less obvious threats.

Balancing Proactive and Reactive Approaches

A proactive stance in EHS recognises the unpredictable. While risk may be calculable, chance requires readiness for the unforeseen. Organisations benefit from integrating chance-based scenarios into risk assessments, building contingency plans for rare but potentially impactful events.

Examples and Standards:

- ISO 31000 provides comprehensive guidelines on risk management, emphasising the need to address both known risks and potential unknowns.

- ANSI/ASSP Z590.3 on Prevention Through Design (PTD) recommends embedding safety into designs to mitigate both risk and chance.

Developing Tools for Safer Systems: Moving Beyond Traditional Risk Management

Harnessing Technology and Data-Driven Insights

Modern EHS systems increasingly rely on technology. Predictive analytics, IoT sensors, and real-time data monitoring offer proactive alerts for potential risks, while data-driven insights help organisations to adapt quickly.

Example: Companies like Siemens use digital twin technology to simulate potential scenarios and manage equipment hazards virtually. Such tools help address both risk and chance by offering a controlled environment to predict possible outcomes.

Scenario-Based Training

Implementing scenario-based training, whether through virtual reality (VR) or traditional drills, enhances employees’ situational awareness. By encountering “unlikely” but high-impact scenarios in training, employees gain the experience needed to respond effectively in real-world situations.

Policy and Procedure Reviews

Routine reviews of EHS policies ensure they’re attuned not only to high-risk but also low-chance events that can have significant consequences. This review should consider whether existing protocols address both calculable risks and random variables.

Examples:

- VR Training in Oil and Gas: Companies in high-risk industries use VR to prepare employees for low-chance, high-impact events.

- Digital Alerts and Monitoring: Real-time data systems in sectors like mining or manufacturing create alerts when unusual patterns are detected, offering an added layer of security.

Competence Development: Building Intelligence in Risk Identification

Knowledge and Skills Training

Competence in EHS goes beyond compliance-based training. It requires employees to develop skills in hazard recognition, dynamic risk assessment, and situational awareness, preparing them to respond even when risks appear negligible.

Empowering Decision-Making Intelligence

Critical thinking in EHS is essential for employees to make judgment calls. Developing this intelligence helps employees weigh “playing safe” against “taking no chances.” Decision-making intelligence is about equipping employees with both data and discretion.

Encouraging Psychological Safety

A psychologically safe environment encourages employees to report hazards or potential issues, no matter how trivial they may appear. Cultivating this culture boosts collective intelligence, creating a safety net where both risk and chance factors are openly discussed.

Reference Standards:

- ISO 45001 encourages active worker involvement in hazard identification, recognising the importance of workforce engagement in EHS decision-making.

- Tod Conklin’s insights on human performance highlight the importance of learning from everyday work and “normalisation of deviance,” addressing how to curb complacency.

Fostering Resilience: Preparing for Low-Probability, High-Consequence Events

Developing Adaptive Safety Systems

EHS resilience is about adapting to both expected and unexpected changes. Resilient systems can withstand disruptions and continue functioning even in low-chance, high-impact events.

Balancing Risk Tolerance with Zero-Compromise Zones

Risk tolerance training helps employees understand when it’s safe to act and when to avoid chance altogether. Employees become familiar with “zero-compromise” scenarios, where safety is prioritised even at the cost of productivity.

Embedding Learning in Safety Culture

Building a resilient EHS culture means learning continuously, not just from failures but from daily operations. Conducting incident reviews and analyses cultivates a deeper understanding of what “could have gone wrong,” encouraging foresight.

Case Study Reference:

- In high-stakes sectors like aviation and nuclear energy, resilient cultures operate on a “no chances taken” principle, underlining the value of resilience for both routine and exceptional events.

- The Safety-II framework supports resilience by encouraging organisations to learn from daily successes and failures, viewing routine work as a key source of insight.

Conclusion: The Future of Risk and Chance in EHS

The distinction between risk and chance isn’t just academic; it’s a vital component of a proactive EHS strategy. By clarifying these terms and implementing robust tools, training, and resilience practices, organisations can better navigate the unpredictable.

The story of the cancelled event is a reminder that safety is about valuing life over uncertain odds. EHS leaders must recognise when to “leave nothing to chance,” even if the risk seems manageable. In doing so, they set the standard for a culture where safety isn’t just calculated but respected and prioritised.

References

- ISO 31000: Risk Management Guidelines.

- ANSI/ASSP Z590.3: Prevention Through Design (PTD).

- ISO 45001: Occupational Health and Safety Management.

- Tod Conklin’s work on human performance: Available through his talks and writings on EHS resilience and proactive risk culture.

- Safety-II Framework: Concepts by Erik Hollnagel on resilience engineering in safety management.

Annex: The Fatalistic Approach to LPHC events in Leaders:-

Many organisations do seem to adopt a fatalistic approach to low-probability, high-consequence (LPHC) events, often due to cost concerns or a lack of perceived relevance. Even with advanced risk assessment tools and data, incidents elsewhere are frequently dismissed as outliers rather than wake-up calls. This mindset can stem from several factors, including leadership gaps, insufficient commitment, or an overly pragmatic approach. Here are some strategies that might help shift this attitude towards a more proactive stance:

1. Foster a Leadership Culture That Values Precaution Over Cost

- Risk Mindset at the Top: Often, the tone is set by leadership’s approach to safety. When leaders convey that safety investments are “optional” for LPHC events, it trickles down. Leadership training should emphasise that LPHC events may be unlikely but not impossible.

- Visible Commitment: Leaders can demonstrate commitment by integrating safety into organisational values. Publicly discussing past incidents and highlighting decisions based on “no chances taken” reinforces a strong safety culture.

- Action Step: Conduct scenario-based workshops with leaders to walk through high-consequence incidents. Let them experience the reality of what these events could entail for the organisation, employees, and community.

2. Challenge Cost-Benefit Calculations with Long-Term Implications

- Reframe LPHC Events as Strategic Risks: High-consequence incidents should be evaluated as strategic risks, not just operational costs. A single catastrophic event can outweigh years of cost savings achieved by under-preparation.

- Implement “What-If” Assessments: Encourage a “what-if” approach that includes direct costs (damage control, fines) and indirect costs (reputation damage, litigation) that LPHC events could entail.

- Invest in Preventive Technologies and Resources: From structural reinforcements to training programs, make upfront investments that minimise the potential impact of such events. The upfront cost can serve as insurance against devastating future expenses.

- Example: Oil and gas companies often invest heavily in fire suppression systems, despite fires being rare. Their experiences with incidents globally serve as a reminder of the price of underestimating low-probability events.

3. Integrate LPHC Events into Routine Safety Culture

- Normalise LPHC in Training and Drills: Make LPHC events part of regular training to demystify them. Routine drills that incorporate these scenarios improve muscle memory and build a shared understanding of what could happen.

- Cross-Industry Learnings: Share case studies of industries with high exposure to LPHC events, like nuclear or aviation, which take near-zero tolerance for error. Learning from other sectors can be humbling and provide tangible examples of risk management in action.

- Reference Standard: Use ISO 45001’s clause on Emergency Preparedness and Response as a guiding framework. It promotes a robust approach to preparedness, which organisations can expand to cover LPHC events.

4. Develop Resilience by Shifting from Compliance to Curiosity

- Encourage a Curiosity-Driven Approach: Organisations should move beyond compliance and cultivate curiosity about “what could happen.” This curiosity often leads to deeper inquiry and solutions beyond mere checkboxes.

- Normalisation of Deviance: Often, dismissive attitudes to LPHC events occur when minor deviations from protocols become routine. Addressing this “normalisation of deviance,” as Tod Conklin suggests, means embedding vigilance into the organisational fabric. Regular discussions, audits, and reviews can help identify and address these early deviations.

- Example: In chemical processing plants, curiosity about minute changes in chemical behaviour has led to protocols that prevent rare but severe incidents.

5. Implement Metrics That Track “Precautionary” Safety Actions

- Precaution Index: Develop a set of metrics that track precautionary actions taken against LPHC events. This index could assess elements like emergency resource allocation, training frequency, or scenario simulations specifically aimed at LPHC incidents.

- Scorecards and Accountability: Make these metrics part of a scorecard for EHS and operations teams, tying accountability to precautionary actions. When everyone from the leadership to ground staff is rated on precautionary steps, it incentivises a culture shift.

- Annual LPHC Event Review: An annual “LPHC event review” could become a staple in the organisation’s risk assessment process. Review known LPHC incidents worldwide, evaluating how local practices align with or differ from best practices in mitigating those scenarios.

6. Enhance Communication Channels to Escalate LPHC Awareness

- Incident Sharing Across Facilities: If a multinational organisation has a high-consequence incident at one facility, the information should be immediately shared with all facilities. Centralising incident reports promotes a unified approach to risk awareness and response.

- External Benchmarking and Knowledge Sharing: Create or join inter-company networks where industries can share best practices on mitigating LPHC events. When organisations witness peers facing high-consequence events, it highlights the reality of these risks.

- Example: In the pharmaceutical industry, consortia like the Pharmaceutical Safety Group (PSG) enable companies to share high-stakes incidents confidentially, ensuring all members can learn from such events without direct experience.

Concluding Thought: A Paradigm Shift for Proactive Safety

Addressing the “fatalistic” attitude towards LPHC events requires shifting the safety paradigm from “likely” to “possible.” This means recognising the significance of rare incidents as much as routine ones. By investing in leadership training, embedding curiosity, and using metrics to track proactive measures, organisations can align their safety culture with a commitment to act before chance becomes fate.

Let me know your comments.

Karthik

3/11/24 12Noon.