#266

Personal Note:- 1984-87 was worst period for Industry with such incidents. I wonder 40+ years on, have we learned lessons. Organisations have very poor memory……

Shcherbrina and Legasov in HBO Series. Legasov was Scientist who coordinated with Soviet Leadership.

As we mark the beginning of 40th year of the Chernobyl Disaster on April 26, 1986, it’s a stark reminder of what happens when safety systems, human judgment, and design integrity fail catastrophically. The explosion at Reactor No. 4 in Ukraine’s Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant remains the worst nuclear disaster in history, with lessons that resonate deeply for environmental, health, and safety (EHS) professionals. Let’s unpack what happened, why it went so wrong, and what we can learn to prevent future tragedies. (And yeah, if you’ve seen the HBO series Chernobyl –by the way – you know how gripping this story is, even if it takes some dramatic liberties.)

What Happened at Chernobyl?

On April 26, 1986, at 1:23 AM, Reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near Pripyat, in Ukraine, in what was then the Soviet Union, exploded during a safety test gone horribly wrong. The test was meant to simulate a power outage to check if the reactor’s turbines could keep coolant pumps running until emergency generators kicked in. Sounds routine, right? It wasn’t.

A mix of operator errors, inadequate training, and a fatally flawed reactor design turned the test into a nightmare. The RBMK reactor had a critical weakness: its control rods, meant to slow the nuclear reaction, could paradoxically increase reactivity when first inserted due to a graphite tip design. When operators tried to shut down the reactor after an unexpected power surge, it backfired, triggering a steam explosion that blew the reactor’s lid off and ignited a fire in the graphite core.

The explosion released at least 5% of the reactor’s 190 metric tons of uranium into the atmosphere, spewing radioactive isotopes like iodine-131 and caesium-137. A radioactive cloud spread across Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, and Europe, contaminating millions of acres of land. Pripyat, a city of nearly 50,000 built for plant workers, wasn’t evacuated until 36 hours later, exposing residents to dangerous radiation levels.

The Soviet Response and Cover-Up

The Soviet response was a mix of heroism and secrecy. Firefighters, unaware of the radiation risk, battled blazes without proper protective gear; many, like Vasily Ignatenko (portrayed in the HBO series), died of acute radiation syndrome (ARS) within weeks. Over 600,000 “liquidators” – workers, soldiers, and miners – were drafted to clean up, often at great personal risk. Three engineers, Oleksiy Ananenko, Valeri Bezpalov, and Boris Baranov, heroically drained radioactive water from the basement to prevent a second explosion, surviving against the odds (contrary to some myths that they died).

The Soviet government, led by Boris Shcherbina’s commission, initially tried to downplay the disaster. It wasn’t until April 28, when Swedish monitoring stations detected high radiation levels and pressed for answers, that the Soviets admitted an accident had occurred. This blew the cover-up wide open, exposing systemic secrecy that delayed evacuations and endangered lives. Shcherbina, a key figure in coordinating the response, faced immense pressure and radiation exposure, though his death in 1990 isn’t conclusively linked to radiation.

Helicopters dropped 5,000 tonnes of sand, boron, and lead to smother the burning core, but much of it didn’t reach the target. By May 8, workers drained 20,000 tonnes of radioactive water, and later that year, a concrete “sarcophagus” encased the reactor, later replaced by the New Safe Confinement structure in 2016. The disaster’s cost is estimated at $700 billion USD, making it the priciest in human history.

The Human and Environmental Toll

The immediate death toll was 31, including two workers killed in the explosion and 29 from ARS, mostly firefighters and plant staff. Long-term, the United Nations estimates 4,000–5,000 premature cancer deaths, with 6,000 thyroid cancer cases in children exposed to iodine-131, though exact numbers are debated. An exclusion zone spanning 1,600 square miles remains largely uninhabited, though some wildlife has returned.

The radioactive cloud reached as far as France and Italy, with caesium-137 still lingering in some soils due to its 30-year half-life. Socially, 350,000 people were evacuated, and the psychological toll led to suicides, alcoholism, and apathy among survivors.

Why Did It Happen? Root Causes

The Chernobyl Disaster wasn’t just one mistake but a cascade of failures:

- Flawed Reactor Design: The RBMK’s graphite-tipped control rods and lack of a containment dome (unlike Western reactors) made it unstable at low power and unable to contain radioactive releases.

- Operator Errors and Training Gaps: Operators, under pressure from deputy chief engineer Anatoly Dyatlov, ignored safety protocols and conducted the test in unsafe conditions. They weren’t fully trained on the reactor’s quirks.

- Poor Safety Culture: Soviet secrecy and a top-down culture discouraged questioning unsafe orders. The test was rushed to meet deadlines, bypassing proper oversight.

- Systemic Secrecy: The Soviet Union’s obsession with concealing weaknesses delayed critical responses, from evacuation to international disclosure.

Learnings for EHS Professionals

The Chernobyl Disaster is a masterclass in what not to do in safety management. Here are key takeaways for EHS pros, inspired by the event and the HBO series’ portrayal:

- Design Safety Matters: Ensure equipment and systems are inherently safe. The RBMK’s design flaws were known but ignored. Always advocate for fail-safes and robust engineering controls.

- Training Is Non-Negotiable: Operators must understand equipment thoroughly. Chernobyl’s staff weren’t prepared for the reactor’s instabilities. Regular, scenario-based training can bridge this gap. Also consequences for incorrect operations must be made very clear.

- Foster a Speak-Up Culture: A rigid hierarchy silenced warnings at Chernobyl. Encourage open communication where workers can flag risks without fear. Safety must trump ego or deadlines.

- Plan for the Worst: The test lacked a proper risk assessment. Always conduct what-if analyses and have contingency plans for high-hazard operations.

- Transparency Saves Lives: Soviet secrecy delayed evacuations and global alerts. In EHS, timely reporting of incidents, even at the cost of reputation, is critical to protect people.

- Protect First Responders: Firefighters at Chernobyl had no radiation protection. Ensure emergency teams have proper PPE and hazard awareness, no matter the crisis.

The HBO series Chernobyl (check it out if you haven’t,) vividly shows these failures, from the operators’ confusion to the liquidators’ sacrifices. While it dramatizes some scenes – like the fictional Ulana Khomyuk representing many scientists – it nails the human cost and systemic flaws. The “Bridge of Death” scene, where residents watch the fire, is debated (many were likely asleep), but it underscores the danger of misinformation.

Leadership Under Fire: The Soviet Response and What It Teaches Us

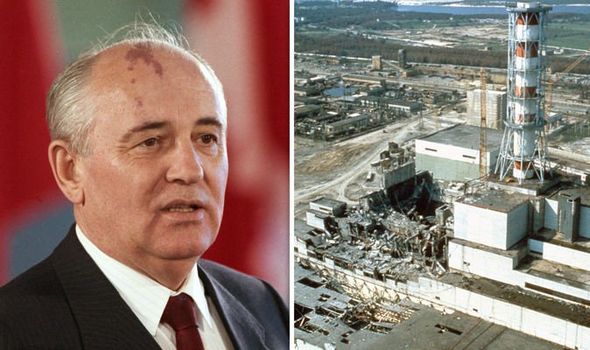

If you thought the technical failures at Chernobyl were bad, the Soviet leadership’s response adds another layer of lessons for EHS pros. When Reactor No. 4 blew, the Kremlin’s first instinct was to clamp down, not open up. Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet leader pushing glasnost (openness), found himself caught in a system wired for secrecy. Let’s break down how the top brass handled it and what it means for safety leadership today.

The Soviet response kicked off with denial. Gorbachev and the Politburo got vague reports hours after the explosion, with some officials calling it a “small fire.” It took Sweden’s radiation alerts on April 28 to force a grudging admission of an “accident.” Gorbachev later admitted he was fed bad info, a symptom of a bureaucracy scared to tell the truth. Boris Shcherbina, sent to run the show on-site, threw everything at the crisis—helicopters dumping sand, 600,000 liquidators cleaning up, a rushed sarcophagus—but often without clear safety plans. Evacuating Pripyat took 36 hours because Moscow hesitated, fearing panic and embarrassment.

Gorbachev’s headspace was a mix of shock and frustration. He saw Chernobyl as a wake-up call, later writing it exposed the “sicknesses” of Soviet secrecy and incompetence. But he didn’t visit the site until 1989, leaning on Shcherbina and scientists like Valery Legasov to handle the mess. The leadership’s mindset—centralized control, blind faith in tech, and obsession with image—slowed evacuations, endangered liquidators, and fueled global distrust. The HBO series Chernobyl captures this tension, showing Shcherbina’s grit and Gorbachev’s distance, though it amps up the drama (no, the world wasn’t that close to total meltdown).

For EHS leaders, this is a playbook of what not to do:

- Own the Truth Fast: Hiding bad news delays fixes and erodes trust. Report incidents transparently, even when it stings.

- Empower Local Teams: Moscow’s grip paralyzed local officials. Give on-the-ground leaders autonomy to act swiftly in crises.

- Listen to Experts: Gorbachev’s team ignored scientists’ warnings about the reactor’s flaws. Value technical input over politics or pride.

- Prioritize People Over Image: The Soviets’ fear of looking weak cost lives. Put worker and community safety above reputation.

Chernobyl pushed Gorbachev toward more openness, but the damage was done. It’s a reminder, that leadership in a crisis isn’t just about action—it’s about breaking through denial, cutting red tape, and putting safety first. As EHS pros, we’ve got to lead with clarity and courage, so our “Chernobyl moment” never comes.

Looking Forward

Nearly Forty years later, Chernobyl’s exclusion zone is a haunting reminder of nuclear risks, yet it’s also a site of resilience, with nature reclaiming parts of it. For EHS professionals, it’s a call to action: prioritize safety, challenge complacency, and learn from history. As you reflect on this milestone let’s commit to building systems where “safety first” isn’t just a slogan but a way of life.

Sources: Information drawn from historical accounts, IAEA reports, and posts on X discussing Chernobyl’s causes and impacts. For a gripping dive into the human story, watch HBO’s Chernobyl.

Karthik

28/4/25