#273

Good to be back from Bombay visit. Boy! Real Bangalore is back with the pleasant weather. (Max 25C, all coming week!).

In the world of workplace safety, few concepts have been as influential—or as debated—as Herbert Heinrich’s safety pyramid. Introduced in the 1930s, Heinrich’s theory suggested that for every major injury or fatality, there were 29 minor injuries and 300 near-misses. This “pyramid” became a cornerstone of safety management, urging companies to tackle smaller incidents to prevent catastrophic ones. But as safety science evolves, critics are calling the pyramid a myth, questioning its data, assumptions, and relevance. So, where does the truth lie? Let’s unpack Heinrich’s theory and see if it’s still a milestone or just a relic.

Herbert Heinrich, an employee at Travelers Insurance, published his ideas in Industrial Accident Prevention in 1931. Analyzing thousands of accident reports, he concluded that 88% of incidents stemmed from workers’ “unsafe acts,” 10% from unsafe conditions, and 2% from unavoidable causes. His pyramid visualized a ratio: 300 near-misses at the base, 29 minor injuries in the middle, and 1 serious injury or fatality at the top. The logic was simple—reduce the base, and the top shrinks too. For its time, this was groundbreaking, encouraging proactive incident reporting in an era when safety was often an afterthought.

The pyramid’s appeal lies in its simplicity. It gave safety managers a clear framework: track near-misses, address minor issues, and prevent disasters. Companies adopted it widely, using it to promote behavior-based safety (BBS) programs that focused on correcting workers’ actions. Heinrich’s “domino model” reinforced this, suggesting accidents result from a chain of events—social factors, human faults, unsafe acts, and so on. Break the chain, like stopping unsafe acts, and you stop the accident. It was a compelling narrative that shaped safety culture for decades.

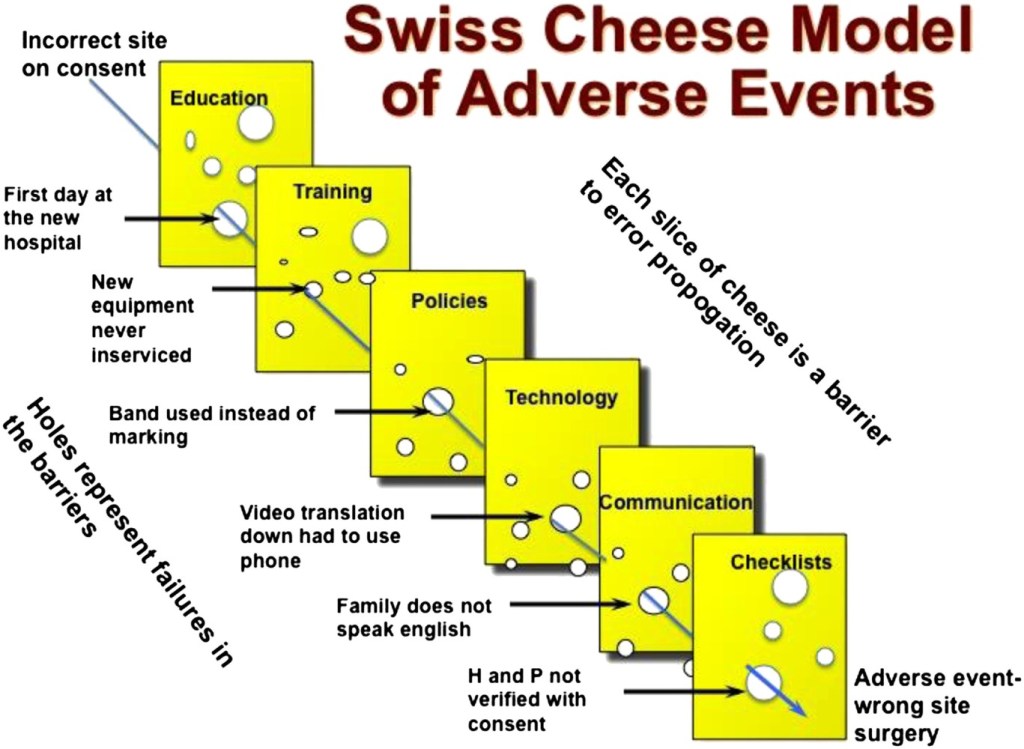

But cracks in the pyramid’s foundation have emerged. Critics argue Heinrich’s data, drawn from 1920s insurance claims and supervisor reports, was flawed. Supervisors often blamed workers to avoid liability, skewing the “unsafe acts” statistic. Heinrich, not a trained safety expert, relied on these biased reports without rigorous root cause analysis. Modern safety science, like James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model, shows accidents often stem from systemic failures—poor training, faulty equipment, or weak safety culture—not just worker error. The 88-10-2 ratio? It’s more a snapshot of one era than a universal truth.

Another issue is the pyramid’s predictive power. Heinrich assumed reducing near-misses would proportionally cut serious incidents. But studies, like a 2003 ConocoPhillips Marine analysis, show different ratios across industries, and minor incidents don’t always predict fatalities. A paper cut and a chemical explosion often have unrelated causes. Focusing on the pyramid’s base can overwhelm safety teams with low-risk issues, diverting attention from high-severity risks, like those in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster, where systemic failures trumped individual errors.

Heinrich’s insurance background adds fuel to the skepticism. Working for Travelers, his focus on worker behavior aligned with the industry’s interest in minimizing employer liability. By emphasizing “unsafe acts,” companies could shift blame from management systems to workers, reducing costly claims. While there’s no evidence Heinrich intended to mislead, his lack of formal safety credentials and unverifiable data (his original records are lost) weaken the pyramid’s credibility. Calling it a myth isn’t about dismissing it entirely—it’s about recognizing its limits.

Modern safety science has moved beyond Heinrich. Models like Reason’s Swiss Cheese or Leveson’s STAMP focus on systemic interactions—how management, processes, and culture align to prevent or cause accidents. For example, a 2018 NIOSH study found that while near-misses can signal risks in some industries, like mining, they don’t universally predict fatalities. Leading indicators, like safety audits or training quality, are now prioritized over reactive incident tracking. This shift reflects today’s complex workplaces, from chemical plants to automated factories.

Does this mean Heinrich’s pyramid is useless? Not quite. Its strength is in raising awareness. It encourages workers to report near-misses, fostering a proactive safety culture. In industries with repetitive tasks, like construction, tracking minor incidents can still highlight trends. But leaning too heavily on the pyramid risks missing the bigger picture—systemic issues often outweigh individual actions. A balanced approach combines Heinrich’s reporting ethos with modern tools like root cause analysis and safety management systems.

For EHS professionals, the lesson is clear: use the pyramid as a starting point, not a gospel. Question its ratios, dig into root causes, and prioritize high-potential risks. The 2013 Sinopec pipeline explosion, driven by poor safety culture, reminds us that blaming workers alone doesn’t cut it. Instead, build systems that support safe behavior—provide training, maintain equipment, and listen to frontline workers. Heinrich’s work was a milestone, but safety science has climbed higher.

What’s your take, EHS community? How do you balance incident reporting with systemic improvements? Share your thoughts and let’s keep pushing for safer workplaces. If you’re curious about modern safety models or want to dive deeper, check out resources like NIOSH or the NSC for the latest insights. Let’s move beyond the myth and build a future where safety is systemic, not just a numbers game.

Karthik

25/5/25 1030am